- Home

- Ivan Srsen

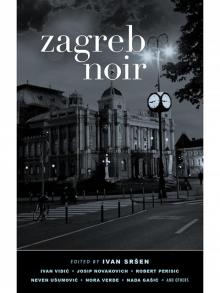

Zagreb Noir Page 11

Zagreb Noir Read online

Page 11

3.

The reason I’ve shared all of this is to explain why Sophia Road was the safer way home. Namely, it was so dark that even the thugs were afraid to go there. They preferred to go down a lighted street or through an adjacent park that was partially lit by streetlights. If once in a while some group or other dared to go through the black woods, they would cover their fear by making loud noises to scare off any wild animals, thereby alerting anyone in the woods to their location. In such circumstances I would simply move about ten or twenty meters away from the road, sit down by a tree trunk, and wait for them to pass. Nothing ever happened to me in the woods, but on the lighted road they twice ambushed me from some bushes and beat me up.

I grew up in the era before cars were allowed down our small side street, so from morning till night a group of boys and I played soccer in the middle of the street, cowboys and Indians in the park, Yugoslav Partisans and Germans in the yards, and Tarzan in the woods along Dubravka Road. I feel sorry for kids who grew up there later and could no longer play soccer in the middle of the street. When we finished college and all got jobs, we each got our own car and life in the neighborhood changed a lot.

Neighbors no longer gathered on Britanski Square, waiting together for the bus and then talking during the ride so that everyone heard everyone else’s business; they no longer got off at stops in groups that grew smaller as they passed from house to house until all that were left were two or three who would stand for a while in front of the entryways to their gardens. Now every morning, each one got into his own car and went to work; after work he parked his car in front of his house and immediately disappeared into it.

That change became more evident to me after I got married, lived for three years in another part of town, in Zapruđe, and then came back to my parents’ house after my divorce. The street was full of parked cars and I had no idea to whom they belonged, and in houses, some close, others farther away, I saw people and had no idea who they were. Nevertheless, I began to hang out with a small group of childhood friends again; we visited one another and I often went out with some of them into town, for fun. Of the original horde of boys there were less than ten of us left. Almost without exception they were the children of state or party leaders, directors, doctors, or military men. One of the few from a different mold was my grandpa, a remnant of a class that had endured a shipwreck of history: before World War II he’d been a wealthy real estate agent, and all that he had left after the nationalization was an apartment that occupied an entire floor of a house in Tuškanac—which he only had for himself because he had managed to evict his fellow tenants by finding them other apartments.

During the separation from my wife, I told her: “Take what you want, but leave me the dog.” As far as the dog was concerned, I was resolved not to get into any negotiations. And that’s what happened. She took everything and left me the dog. A black one, Blackie. Every evening I took him on a walk through the park and the woods for at least an hour, if not two, running some of the way. I was in great shape. After the walk I usually stopped by a friend’s, talked a bit, had one last drink, then went home to bed.

4.

By profession I’m a graphics engineer. I thought about studying painting, but I’m not good with color. So I decided on graphics. Black-and-white, I’m like a fish in water with that. I also have complete control over shades of gray. I’d say that my limitation is maybe that I’m inclined to see other things in life in terms of elementary contrasts.

White: Čedomir. Čedo was born and grew up on my street. He lived three houses down from me. His dad was a major in the JNA—the Yugoslav People’s Army—and their apartment took up a whole second floor. His dad was a good man, but a simpleton. I’ll never forget Čedo’s fourteenth birthday party. That was an important day for him and weeks earlier he’d asked his father to let him invite his friends over. In the end his dad gave in. The agreement was that the birthday party would be in two rooms that were separated from the rest of the apartment, which was where the rest of the family would be. His mom made a bunch of sandwiches. We secretly brought a few bottles of hard liquor. When we got there, Čedo turned out the light, put a record on, and we all grabbed girls and started dancing; when everything couldn’t be going any better . . . Bam!—the door opened and his dad burst in.

“Why is it so dark in here?!” he asked, switching on the light immediately. Everyone froze. His dad was dragging a chair behind him. He slammed it down in the middle of the room, took a seat, and looked over everything around him. After a couple of minutes he grumbled: “What’s wrong? Why aren’t you doing anything? Enjoy yourselves!”

That was too much for me so I grabbed one of the girls and led her off into the other room, where it was still dark. We sat down on the couch, took a swig from a bottle that was hidden behind it, and started kissing. His dad flipped out. When I leaned over I could see him in the light of the other room. He was sitting as if on a hot stove, squirming and craning his neck to see what I was doing, but no matter how much that bothered him he didn’t want to abandon his position, from which he was able to keep an eye on everyone else. It ended with us eating the sandwiches and then all going to the park (we took the bottles with us), where we messed around until midnight.

Čedo was basically a nice young man, which made him different than all the others. He got nothing but the best grades in school, and his parents never had any problems with him. He got his degree in electrical engineering on time, finished his military service, got a job in the Rade Končar electronics factory, and soon after got married. He and his wife had two children very quickly. From his job he went straight home and didn’t go out till dawn when he had to work the next morning. His wife was pretty and nice; I saw her often when she took the children to the park to play. Čedo seemed like he had all he’d ever wanted, and the only thing his wife had to put up with without grumbling were his frequent trips to transformer stations and similar installations throughout Yugoslavia.

His father had died before he got married, and so he took care of his mother until he buried her too. In fact, the last time we spoke was at the wake in his apartment before her funeral.

Black: Krunoslav. On the ground floor under Čedo there lived another character from our generation, who was the complete opposite. Kruno was the only one with whom no one hung out. His mother was to blame for everything, but in the end it didn’t matter who was to blame because all that remained was what was important—that no one hung out with him. In the days when the apartment on the ground floor was still shared by four tenants, Kruno’s mother had handled the relations between them by shouting almost every day at someone so loudly that it could be heard up and down the street. And this was how she handled her relations with her husband, who was basically the same as her. Before we started going to school and still played in the middle of the street, his mother watched from the window and if we argued she didn’t hesitate to run out of the building, grab whomever she thought was doing something to her son, pull his hair cruelly, and slap him. Soon we ran from Kruno’s mother whenever she appeared for any reason, and she forbade him from playing with us, so he ended up sitting in the room in which they lived and stared through the closed window while we chased each other and shouted in the street in front of the house. His mom was a really wicked and jealous person who hated the whole world, thinking she was better than everyone else, which necessarily resulted in her being bitter and hostile. To make matters better (or worse), her husband was a mechanic in some shop and wasn’t a caring and homely kind of guy; she didn’t work, and so they were really poor. And while everyone around them made progress in some way day after day, they didn’t go anywhere.

Kruno barely finished elementary school and was the only one of us who didn’t go on to prep school but enrolled in some vocational school for economics, but didn’t finish. When he was seventeen he ran away to Germany and was gone for two or three years. People said that he made his living in Germany from male prostitution. I ca

n’t confirm that this was true, but it seemed convincing and believable, if nothing else entirely possible because no one who knew him had ever seen him with a girl. He came back at some point and got mixed up in some shady business. On account of him suspicious men would come to our street. Every so often some kind of fracas could be heard in his house. A few times the police had to get involved, and the cops would come around the neighborhood and ask questions and so on. He was the reason no one could leave nice tools, an unlocked bicycle, or other such things in their yards. They would simply disappear.

One evening, as I came home from walking my dog and passed Kruno’s house, I noticed an unfamiliar car parked on the far side in some deep shade, shielded from the streetlights by treetops. Four dark figures sat inside, and kept quiet as I passed. No one with ordinary eyesight would have seen them, but I could tell they were very big. And they couldn’t have been waiting for anyone else but Kruno.

Instead of going inside my house, I sat down in the yard on the stoop in front of the entryway, opened a beer, and started leisurely sipping it. After a while, Kruno appeared. I went out into the street, stopped him, and invited him to my place. We sat on the terrace and waited for over an hour until the unknown car gave up on the ambush and drove away. Kruno was moved to tears for not having stumbled into the arms of the men who’d been waiting for him.

After that he disappeared for about a month. I didn’t need to check whether he’d come home because an electric drill disappeared from where I’d left it on the same spot where I’d recently sat waiting for him. I went to his place straight away and entered without knocking. His father had been dead for a long time, and his mother had become a withered, hunched old woman. The two of them continued to live in a single room behind the bathroom on the other side of a common hallway while another tenant on the ground floor managed to gain possession of the rest of the rooms and turn them into a very nice apartment. They would have moved out too, if it were possible to agree with the other tenants on anything. The drill was lying in the middle of the table. I walked up and grabbed it. Kruno mumbled: “I borrowed it! I just borrowed it! I was about to bring it back!”

“Right!” I said, and went out without saying goodbye.

That evening I told Nikša what had happened.

“Damn. About a month ago I had to go over to his place like that to get a car jack back!” Ice cubes were melting slowly in our glasses of whiskey as we talked. “Doesn’t he get bored stealing things around the neighborhood? We all know he’s the only thief in the area!”

Then the topic of conversation switched from the neighborhood to its history.

“This part of town is cursed! Have you ever thought about the houses we live in and who lived in them before? When Austria-Hungary fell apart, all those nobles and Austro-Hungarian generals went off to Vienna or Budapest. When the old Yugoslavia fell apart, the Serbian merchants went off to Belgrade. Many of the mansions belonged to rich Jews. The Ustashas put them in camps and moved into houses and apartments where there were still warm bedsheets, unironed laundry, and closets full of clothes. Then the Partisans came, and the Ustashas fled. If they didn’t make it to South America, they probably died at Bleiburg. And all that in less than seventy years! Now we’re here, but I don’t know whether it’ll be for long . . . This part of town is on the windward side of history and might get blown away.”

5.

I’m not interested in politics, don’t like them, but even a blind man would notice that something was going on, that something bad was simmering. In our neighborhood, in Tuškanac, everything looked normal, but down in the city things were boiling over. Banners suddenly popped up everywhere; every day there was some assembly, and traffic had to be diverted to bypass it. On one of the TV channels there was always someone giving a speech in lofty tones, so that I would immediately change the channel. The people in the cafés acted like they were in some third-rate movie about a universal conspiracy. Every day the front pages of the newspapers were full of headlines that looked like reprints from fifty years ago . . .

“Damn,” I said to Nikša, “none of this has anything to do with me. I’m the offspring of a class that’s already been smashed by the waves of history anyway. Come what may, I’m not going to be a part of it.”

Still, there are things that sweep everyone up in them, and no one can get away. An air-raid warning. The first time the sirens started wailing over the city to announce the danger of an air attack, no one needed to be told what was going on. So we still live in a country where people immediately recognize an air-raid siren, even if they’ve only heard about it.

It was a nice, sunny day. I went out of the house and sat down on the stoop out front. As soon as the sirens died down a silence took hold like I’d never heard before in my life. I’d brought out a bottle of beer, and I opened it. It must have been a Saturday or a Sunday or some state holiday because I wasn’t at the office. My dog came and sat down beside me and we both listened. Even if Tuškanac was the quietest part of Zagreb, you could always hear the noise of the city in the distance. But that had disappeared too. There were no cars on the road, and the public transportation had stopped running. The best definition I know of silence is that it’s when you can hear everything, even from a great distance. I heard the song of some little bird that must have been three hundred meters away. It sounded to me like a nightingale.

Even the wind had stopped. You couldn’t hear a leaf. It seemed that the entire city was paralyzed with expectation. I strained my ears, awaiting the sound of the distant approach of aircraft, and wondered whether I would hear them at all or if the first sounds would be of bombs exploding. These modern airplanes, faster than the speed of sound—I don’t know what they sound like when they fly over. My mother often told me that during World War II she was most afraid of the roar of bombers. Up to her death, she never recovered from the panic that had seized her when Flying Fortresses had roared overhead. I wondered how much a modern air attack differed from those that my mother had lived through.

I suddenly heard something that I didn’t recognize. A little ways off from my house, there’s a bend in the street, and something was approaching from that direction. The sound of something like the thud of iron-shod boots, the scraping sound of house slippers, and some kind of clinking . . . From the bend in the street there appeared three figures who looked like they came straight out of the Mad Max movies. One was completely bald, the second had a mohawk, and the head of the third was covered by a helmet. They were tall, armed to the teeth, and looked ugly and dangerous. The tallest one was bare down to his waist, dressed in camouflage pants and army boots. He had two machine-gun belts slung crosswise over his bulging bodybuilder’s chest, and carried a MG 42 as if it were only an air rifle. The second was dressed in a combination of fatigues and denim clothing, tennis shoes, and some stylish sunglasses. He was carrying a double-barreled shotgun. The third one had thrown a bulletproof vest over his bare chest and had a small pistol; all three of them had Motorola portable radios, bayonets, and revolvers in holsters hanging from their belts. I looked them over curiously as they walked by, at the ready as if they were moving through enemy territory. You know—one looking ahead, and the two behind him looking from side to side with their weapons locked and loaded. As they passed, all three of them turned their heads toward me. I raised my bottle as if toasting them and waited a little for them to move on before I took a drink.

Crazy shit! I thought. This isn’t going to end well!

About an hour later the sirens signaled the end of the air-raid warning. Nothing had happened. A futile warning. The city breathed a sigh of relief.

The next warning happened at night. A woman from the office was visiting me and instead of rushing down into the cellar, as prescribed by the regulations, we immediately went up to the attic, then climbed up a ladder and through a little window onto the roof. We climbed up to the very top and sat down between two chimneys. Just as I never play the lottery because I’m certain t

hat I will never win anything, now I was sure that there was no chance of the first bomb hitting my house. The night was beautiful. Over the treetops of the park we could see the whole city laid out before us. The streetlights had been turned off and for the first time I saw it in nothing but moonlight and starlight, and the stars had come out in numbers like one sees in the summer on distant Adriatic islands. That heavy silence settled down, punctuated now and then by bursts of fire or single shots.

A story had spread that Serbian snipers were operating in the city, and the gunfire suggested that the story was maybe true. Maybe it was the snipers shooting, or maybe someone was shooting at them. We didn’t know. Only years later did I run into a guy who told me that he’d been in an observation post in the vicinity with some soldiers and had noticed when I climbed up on the roof with my lady friend. They had night-vision binoculars and could see us clearly. He said that they could have picked us off clean and that they had a bitter argument about whether they should take us down or not, whether we were some phantom snipers or not, but fortunately—as they saw that we didn’t have anything that resembled a weapon on us—the naysayers won out.

After the first air-raid warning the city changed its appearance. In the morning windows appeared covered with packing tape and sandbags had been stacked next to cellar windows and doorways. Many windows kept their blinds lowered or shutters closed throughout the day as well. A great number of people walked around the city dressed in various kinds of pseudo-military uniforms, carrying weapons. Suddenly there were private automobiles without license plates; some were painted with camouflage splotches, some had crudely cut openings in the top along which pintle mounts for machine guns had been welded. It wasn’t uncommon to see a luxury car, say a Mercedes, with a hitch that wasn’t pulling a trailer but a wheeled, triple-barrel automatic cannon. The air-raid warnings provoked a few minutes of panic during which cars shot through red lights at intersections to get off the roads, pedestrians ran into the nearest buildings, and most people who were out somewhere found themselves in a stampede to get down into cellars which functioned as improvised shelters. After a few minutes the city relaxed, and no one could be seen and nothing could be heard anywhere.

Zagreb Noir

Zagreb Noir