- Home

- Ivan Srsen

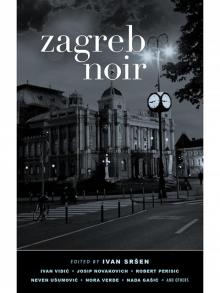

Zagreb Noir Page 7

Zagreb Noir Read online

Page 7

“This is how they should look,” the woman says, and chortles again.

“Shouldn’t they be a bit freakier?”

“No, this is just great.”

I sit down at the table next to theirs. I have to hear some laughter. The waitress comes and recites the menu although everything can be read off the tablecloth. I order Zagreb schnitzel and a beer. The wood-paneled walls make me feel like I’m suffocating. The little signs on them add an edge of queasiness. I drink the beer but leave the meat untouched. I pay and leave.

The clock on the main square shows nine. The right time for a visit. Forty years later. My hand in my pocket squeezes the switchblade and I think: Should I make Elza pay for what she did to me? I’ve been living with the conscience of a murderer for so long that it wouldn’t be hard for me to pass judgment on her too. I cross the square and walk along Jurišić Street.

* * *

I rushed out of the apartment, ran along Jurišić Street, crossed the square, and turned down Praška Street. My lungs hurt and my head drummed. I tried to remember how much money I had in my purse. Would it be enough for a ticket to Šibenik? What would I do when I got there? Where could I hide? The police would find me. Elza would tell them everything. Or maybe she wouldn’t? Did she love me so much that she’d take the blame herself?

I ran through Zrinjevac Park. The shade tempered my fear. It was quiet, perhaps too quiet. No one to be seen anywhere. If the police were on my trail, they’d immediately notice a woman running. I left the sidewalk and walked quickly over the lawn and through the dying ornamental bushes, went around the pavilion, and continued on to the railroad station. A train was leaving at eleven.

Once home, I told my father I’d passed all my exams and had a month’s vacation. He believed me, and I spent days feverishly leafing through all the papers looking for news of a fatality on Jurišić Street. I wrote to Elza, but a reply never came.

* * *

I arrive in front of the building where all the highs and horrors of my youth took place—experiences I kept reliving again and again, year after year, feeling there would be no end to it, until my diagnosis came and limited my shameful life to several weeks, or months at best. The realization that everything will soon be over has brought me here to this building.

In place of the old five-story building with its massive wooden door that was locked with its rusty handle at ten in the evening, there now stands a seven-story, steel-and-glass edifice, threatening and cold, with a large opening instead of the former vestibule.

I go in and stand at the doorman’s booth which is protected by thick greenish glass. A young man sits reading a book under the neon light. He looks up, brings his mouth to the microphone, and says in a metallic voice through the speaker: “Good evening. How can I help you?”

I ask him if Elza and Martin Heigl still live at this address, hoping that the tenants are perhaps still the same even if the building’s exterior has changed.

“I’m sorry, madam, there are only commercial tenants here,” he says mechanically, and picks up his book from the desk again.

“But where are the old tenants? Do you know where they moved to? And when was this built?” I bombard him, as a sense of panic starts to creep over me. It seems all my plans of the last few days have been futile.

The doorman puts his book down on the desk again, reluctantly gets up, and comes out of the booth. He stands next to me in that passageway that leads to the rear courtyard, where there were once wooden sheds, and now a nicely paved parking lot. He tells me about a fire that destroyed much of the building forty years ago, and also about an old lady who often drops in at the beginning of his night shift, recounts the past with sadness in her voice, and talks with even more sadness about her bleak life in a high-rise building on the city’s outskirts.

“What’s her name?” I ask.

“Katica. She’s the one who told me about the fire. But you know, that all happened long before I was born,” he says with a smile.

“Has she mentioned Elza? Or Martin? You don’t have Katica’s address by chance, do you?” I desperately ask.

“Madam, honestly, I don’t know anything about Katica either. For me, she’s just a crazy old lady who comes here, stands where you’re standing now, and talks to herself.”

“What else does she talk about?”

“Oh, nonsense. She talks nonsense, so I don’t make any effort to listen.”

“But surely you picked up something?”

“Well, yes, she’s constantly going on about the fire, and about her friend whose apartment she heard an argument in, and about some student, and then about the fire again. She cries a little for that friend who died in the fire. And then she’s gone. That’s all I know.”

“How did the fire start?” My voice is beginning to tremble.

“I’m not sure. In any case, it was after a nasty fight the couple who died in the fire had. The old lady claims it was arson and suspects her friend’s husband. I find it all a bit far-fetched, but I don’t want to start arguing with her. You know what old ladies are like—they’re just waiting to leech onto someone.”

“Did the whole building burn down?”

“No, but it was so dilapidated that the council decided to demolish it and rebuild. And the new building fits in just fine among the older ones, don’t you think?”

“Yes, I guess so,” I say, feeling a shudder come over me, and then I realize I might be able to persuade him to show me around. “Could you perhaps let me see some of the building from the inside? I’m an architect, and this is a fascinating example for me. I’m currently working on the interpolation of a building in the old town of Šibenik.”

“I’m not actually allowed to, but there’s nothing to steal anyway. The offices are all locked,” he tells me abruptly, as if he’s just made one of life’s difficult decisions.

I follow him into the building. From somewhere in the distance there comes the humming of vacuum cleaners.

“Let’s take the elevator to the fifth floor. The cleaning ladies have finished up there. It would be best if they didn’t see us,” he says almost apologetically as we get into the elevator.

Aluminum banisters and glass. As we’re rising, my stomach cramps up, and my head tries to sort out everything he’s told me. The elevator comes to a halt with a metallic clack and we get out. The landing has been enlarged and the entrances of the four apartments are gone. In their place I see a wood and iron desk and a corridor stretching off to the left and right. Neon lights reflect off the smooth imitation-stone flooring.

I turn right and go past a row of closed glass doors. Behind them is darkness. My heels tap in time with my heart. My palms are sweaty and I clench my fists spasmodically. I feel my fingernails digging into my palms as I try to work out where my room used to be. Perhaps where that wooden door is ajar—the only one in this silent realm of glass, neon, and metal.

“Why is that door open?” I ask the doorman.

“That’s the lumber room. We call the door the Gates of Hell because, however you shut and lock it, it always opens again by itself. Something’s probably wrong with the lock, but since it’s not an essential room no one’s ever had it repaired.”

I look into the dark streak grinning at me from behind the slightly open door. I sense this was my student room where Elza used to visit me whenever Martin was away. Yes, this is it. I am drawn to the door. Elza and Martin’s fight with slapping and crying echoes in my head. I hear someone shouting, “Call the fire department!” and the doorman yelling after me: “Madam, you can’t go in there!”

I step in through the noise. The door sucks me in. I close my eyes for a moment, and when I open them again I see Elza’s round face right above mine. I’m lying in bed, lit up in the morning sun. Elza kisses me tenderly.

“I love you too, Elza,” I whisper.

PART II

KKNOCKING ON THE NEIGHBOR'S DOOR

Horse Killer

by MIMA SIMIĆ

> Dubrava

Translated by Ellen Elias-Bursac

Behind the well-worn counter of the hotel’s front desk and the beehive of key cubbies, there is a small office. The furniture—a green-surfaced particleboard desk, a classroom chair that survived the eighties, a rickety cupboard spilling loose-leaf binders, and a hotel safe with a combination lock. The walls are yellow with smoke and decades of breathing. There are no pictures on the walls, only a little window looking out on the hotel’s neon sign. The only item at the hotel that keeps pace with the times—the fixed surveillance camera aimed at the safe at a diagonal tilt from the room’s upper corner. It records this frame twenty-four-seven; the videos are stored on the camera’s memory card, and every forty-eight hours the new material overrides the old. At least that’s how it has been for the last few months, since I’ve been living here and working off my room fee by sitting at the front desk, repairing this and that around the hotel, changing faucet washers and shower heads, fuses and lightbulbs, fishing costume jewelry out of the drains, tidying the rooms, and distributing the threadbare bed linens and coarse pink sheets of toilet paper that are only manufactured for the nameless hotels on the edge of town. A surveillance camera and a safe? In hotels like this, all a person is likely to find in the safe is the owner’s farewell letter or a roll of three-ply toilet paper. This hotel is so unremarkable (no contract and negotiations, no prying neighbors) that it’s better living here than renting an apartment. A hotel with a black hole where the stars should be, with one of those cheap neon signs that either burns out regularly or shines with gaps, spelling HOT or HOE, and promising the nonexistent tourists a wild fling and take-home syphilis. It has no restaurant, no kiosk, not even a café—for years you can nonexist here, below the radar, off the grid. It must be thanks to the long-suffering tenants that the hotel limps along as it does, against all reason. In fact, it seems to be living its life quite solidly; like a benign growth with a very resilient system of recharging.

Just as during the war, sometimes there is no running water and hot water is a rarity. The water pressure in the pipes is best in the dead of night when the sinks and toilets everywhere are dormant. But people quickly realize there’s no point in waiting. In stale dreams and under a brown synthetic blanket, one’s body comes to a simmer countless times before dawn. And there’s no ventilation to cool the room or at least cocoon the sleeper with its hum. The thin walls leave the sleeper enveloped in sounds, like those paper partitions in the one-story houses in Japanese movies behind which neither body nor voice can hide. You put your ear to the front desk, as to a train track, and you know what’s up at the hotel. You know even more if you don’t sleep. Who has escaped a spouse, children, family, debt collectors, or the police. Who steals, who begs, who sleeps around, who gives the beatings and who gets them, who stares all day long at the ceiling, at the wall, at the warped parquet floor, and forgets to breathe. Who snores, who paces, who talks, who cries out in their sleep. When you don’t sleep, the foot on the gas pedal gets heavy, traffic lights change a little slower, and the signals leap out at you just a second too late, but life is clearer and louder than at any IMAX movie. And it stinks, insufferably.

Midnight passed hours ago, and no longer can the voices be heard through the walls or the water in the pipes. In the small room behind the front desk the air is thick and stale so I breathe thriftily like a diver. For a moment I hold my breath and think I am in tomblike silence. But tomblike silence is not the absence of sound. It is a fabric of peripheral sounds at a frequency beyond the range of the human ear. Wormwood crackling in the oak of a coffin lowered into a concrete chamber. Grubs squirming in rotting flesh. A cobweb undulating in the nooks of a grave, mold surging. These sounds do exist somewhere, someone hears them. There is no absolute silence, not in these black holes nor in the five-star ones. All it takes is putting an ear to them.

I push the chair noiselessly over to the safe, place it squarely in the frame. I sit and look up at the dark protruding eye of the camera. And then down again at my hands. There was no water last night, despite the apocalyptic flood still raging outside, or maybe because of it. My hands stay in my pockets; edging my fingernails is a crust of blood and in the circular furrows on my fingertips, the pixie dust of gunpowder. From my pocket I finally take the revolver, shift it from hand-to-hand; it’s army issue and sits well in my palm. It has survived the Foreign Legion, wars—both intercontinental and local—urban and rural confrontations, hand-to-hand; and over picket fences, break-ins into full houses and empty flats, holdups of bookmakers and gas stations. The grip is grooved. Scars from wars, or notches. It has the heft of a loaded gun, but when I cock it and pull the trigger, it comes up empty. As if after a protracted, serious illness, it has nothing left to retch. No fire or pain, just sound. I look up at the camera again, check to see the red light pulsing, pull a breath up from the depth of my diaphragm, and for the first time in the story, I speak.

The plan was drawn up long ago; all that was needed was the flick of the flag in the air, the signal. And that, as it happened, came from above. For several weeks, more frenzied than ever, the media had been warning of impending climate change, cyclones of hot air to the north and the shrinking of the polar ice cap. Screaming headlines, white-hot weather maps, professional analyses, and caricatures in which the sun, deep in the polar realms, rests between the sweaty buttocks of glaciers. And this time it was really happening. In record-breaking heat, the permafrost crackled and gasses that had been trapped there for centuries flashed and snapped like fireworks. Boundless curtains of dust blazed on all sides and hundreds of meters up in the air they swirled again into clouds. Dense and toothed. Launched by winds and pressures, monitored closely by satellites, they inched southward in fleets. Along the way they sucked in the skeletons of birds, airplane debris, meteor dust, until finally, dingy and greasy from the journey, they ran aground on the city skyscrapers, blackening a stretch of sky from the massive shopping complex in the west all the way to the army hospital in the eastern part of town. They sizzled with electricity, spewing sparks. And, overnight, the climatic circuit panel blew its winter fuse and summer plugged in.

It hit on a Sunday morning like an eighteen-wheeler, its hot breath sweeping people from the street, battering windows and doors. Bears at the zoo reeled on the verge of cardiac arrest around the empty wading pools, their biological clocks shot. Bees collided, befuddled, and pelted people and houses like living hail. The Sava shivered in its riverbed and the window panes on the office buildings vibrated even when there was no wind. Within a few days, amidst the crisis of emergency interventions and grimmer and grimmer forecasts, hope spilled over into panic and people rushed to the gas stations, filled their tanks and cans, stuffed photographs into plastic bags. The traffic jams on the roads leaving the city grew wider and longer, more anxious, and at night there were cascades of light coursing out of town. No one had expected the end of the world quite so soon, but people adapted quickly, they were resourceful. Big and small businessmen left, one by one and in groups, in small cars and in large cars. Their own, borrowed, stolen. Family homes with front yards that had been cultivated for years were abandoned, and along the way the yards of others were invaded. People jumped to aid their neighbors in distress, proffered helping hands, and stabbed each other with knives and screwdrivers. The shelves and display cases in the grocery stores were emptied. Just in case, signs were posted announcing inventory, collective vacations, a speedy return. They shut down restaurants, striptease bars, night clubs, and cafés—all but one. The one to which the Horse had been coming every day for months.

Right from his first day there he found his spot. A booth in the shadows from which he could survey the entire place, all the tables, the doors to both restrooms, and the bar. His own little piece of dark from which he scanned the waitresses and the guests. When he wasn’t there, the booth stood empty, on indefinite reserve. Why they dubbed Pero Vidović the Horse, I don’t know. Maybe because he looked like one: widesp

read eyes, broad nostrils, a long deadpan face, long powerful legs. Where I’m from, people used to say a person is stupid as a horse, but I’m from Dalmatia while he’s from Bosanska Posavina and who knows how smart the horses are there and what properties the local people ascribe to them. Maybe his father was the one who gave him the nickname in childhood out of faux tenderness, for putting up with his beatings. Or it was his best friend, or his brother, as they raced each other down a dusty street, never guessing he would later choose a path such a noble animal has never yet trod.

All the tram lines lead there. By day this is where they turn around and at night, their terminus. When the state of emergency was declared it became the tram dump. On the last tram, displaying the Out of Service sign instead of a destination, the driver and I ride alone to the Dubrava terminus. The blue awning of Voljeni Vukovar puffs noisily in the wind, brown, wicker chairs stacked one on top of the other shiver, bound with steel bands to the iron railing. So they won’t blow away or be carried off by someone on the run. A gust of wind opens the door. Inside the air is stale and warm. The silence seems temporary, like an awkward lull in a conversation or a gap in a radio broadcast.

I go up to the bar, mellow, as if this is the most normal of days. The waitress is not expecting any more customers. Surprised, she halts midstep, forgetting to say hello. I sit at the bar and her surprise quickly melts into indifference. She asks what I’ll have. I order a whiskey, or anything with the equivalent alcohol content. Some treat their insomnia with it, but mine, deeper than the Arctic Ocean, drinks it readily like rainwater. As if we’re at a firing range, the waitress lines them up and I take them down. Exhaustion is flight. Exhaustion frees. The feeling is correct, accurate, and truthful. From a distant corner of the bar a gaze slices into me. I do not have to turn, I know Pero the Horse is there.

Zagreb Noir

Zagreb Noir