- Home

- Ivan Srsen

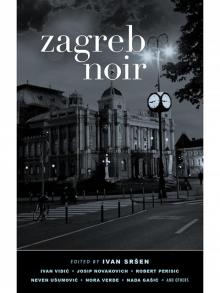

Zagreb Noir Page 9

Zagreb Noir Read online

Page 9

I just walked. I walked and nothing happened. Everything was calm, and I had to maintain that calm, walking click-clack. I was a little surprised, mostly by the silence in my head in which I heard my own steps as I walked click-clack in my old shoes which wouldn’t have been bad for tap dancing.

And maybe they were tap shoes, I thought, I bought them at a flea market—click-clack—and what do the people know there?

When I made it past the barracks I felt great relief. As if I’d put the whole war behind me. Then, after another two or three hundred meters, I was stopped by the police.

“Where are you going?!”

I wiped the sweat from my brow. “Into town.”

“No you’re not!”

“But I need to go into town.”

I stood there as if I believed he was going to let me pass anyway.

“You can’t. Are you deaf?!”

“So where can I go if I can’t go there?”

I had to get into town, I had to get ahold of someone, otherwise I would go crazy in my little kitchen. Besides, getting back home wasn’t going to be simple.

The policemen were probably protecting some bigwig, because what was on the other side of them couldn’t have been worse that what was behind me.

“So where will I go now?”

“Over there there’s a shelter. Didn’t you hear the sirens?!” the policeman said, angry that I wasn’t afraid of him.

I found the shelter and took a look around. A cellar. Iron bunk beds. Bad air. Bad light. Children’s voices. Then I had a smoke in the doorway. I recognized someone I knew; I didn’t know him well, but his was the first familiar face I’d seen since I got there. So I went up to him as if he were an old friend. He was wearing John Lennon sunglasses, I would see him in bars on Vrhovec Street, where people listened to Can and Amon Düül, kraut-rock. After some small talk, I said: “C’mon, let’s go to your place and watch some TV until the emergency is over!”

He didn’t want to; he said he lived with his parents. He moved away from me a little.

The emergency sirens lasted a very long time. I ran out of cigarettes and started looking for the guy with the John Lennon sunglasses. He’d disappeared. I went around the shelter trying to bum one. From mothers with children. They were polite.

As soon as the all-clear sounded, I kept going toward Britanski Square.

At Darko’s I pressed the doorbell. It was silent.

I kept walking down Ilica Street, and bought some cigarettes along the way. The occasional civilian looked straight ahead. I sought their gazes. Nothing doing.

Uniformed men were watching everywhere, their gazes stretched out into the distance.

I went on, click-clack. It occurred to me that my shoes weren’t good for war at all.

I finally made it to the center of town. It was like nighttime as far as the number of people was concerned. I made it to the Cinema Club and saw that its windows were boarded up. They had closed too?

“Wild, wild horses, couldn’t drag me away . . .” The music frightened me when I opened the door. After a while I realized that the boards over the windows were for the blackouts.

There were about fifteen people inside. I looked at them eagerly. Half of them were armed. The other half were druggies. They were sitting as they always did, which gave me a feeling of security. Nothing was new for the junkies; their battle was always the same.

There was a pool game going on. Someone broke the balls with a powerful shot.

But there wasn’t anyone for me to talk to.

I ordered an absinthe and smoked at the bar.

One of the druggies came up to me and said: “Need something, buddy?”

“I’ve got all I need,” I responded.

I drank a second absinthe, waited, and smoked. The smoke wafted through the light of the bar.

As the windows were boarded up, there was no way of knowing whether it was day or night, what time it was, or what was going on in the world outside. You were rocked gently, like being below deck on a ship. The Cinema Club was a long ground-floor barracks, but I felt as if we were somewhere deeper below.

I continually wavered between another absinthe and getting up and leaving.

I needed to go, but something kept me from it.

Then there was the serpentine sound from above once again: the air-raid warning. That meant the trolleys and buses would stop running. I decided to wait a bit longer. Two months ago this was the “in” place for the alternative crowd. People should have been arriving right about now. Theater people, musicians, barroom philosophers—where are you now?

I went to the door, peered outside, and saw that it was now dark out.

I went back to my seat.

There were five kilometers between me and my little room, click-clack. Every so often there were gunshots—sometimes a single one, sometimes a burst. They could be heard inside through the boards, like staccato farting. I swallowed a stress pill; I had some of those.

The junkies were simmering here and there around the tables: each one was sitting with his legs stretched out, not looking at anyone. Their cigarettes burned down slowly between their fingers. A few guardsmen were playing pool under a funnel lamp. One of them went up to the bar to ask for another token, and the bartender disappeared somewhere to get one.

“Do you work here?”

“No.”

He drummed his fingers on the bar. He looked at me as if he were wondering what I was doing here if I didn’t.

Then the bartender appeared from the back room and gave him the token.

* * *

When Darko came in, it was like the coming of the Messiah.

“Where’ve you been, man?!” I asked.

“Iggy!” he shouted.

He looked me over as if looking at a monument. He said: “Man, I can’t believe I ran into someone I know!”

“You too, huh?”

After we patted each other on the shoulder, we sat down at a table. “What’s going on?” we asked in unison.

“I signed up for the Croatian Defense Forces,” Darko said.

“Really?”

“Today!” he said, opening his eyes wide and nodding.

“Aha,” I said, not sure what to say.

“What the hell . . .”

“Well . . . right.”

“I had to,” he said. “I was watching television and . . .”

“I know . . .”

Ten or so days ago I was on an island on the coast watching television, terrible news, and said, “I’m going to join up!” But then my mother attacked me with her artillery. She’s a very difficult person, I can’t deal with her.

Darko said: “They told me they’d call me up when they get weapons.”

“They don’t have any?”

“No!” he said, staring in front of himself.

“Hmm.” All things considered, that was pretty worrisome. But maybe not for him at the moment.

“What do you think? Are they going to call me up?” he asked.

“How should I know?” It was like they made a mistake by not calling him up right away.

“What the hell,” he sighed. “I signed up.”

He seemed to have it a lot harder than I did—I didn’t really have any problems. He was drinking pretty quickly. He ordered a spiced brandy and beer.

I patted him on the shoulder. “It’s so good to see you again.” Then I added: “I don’t mean like in that song by the Fossils, but really.”

He shook his head with a smile. “Oh man, I’ve been here since late July. I was in Germany. I thought about going to the coast, but gave up on that . . . And none of the gang is here! Only people from Zagreb,” he said, looking at me as if he were about to hug me, but didn’t.

I nodded, and he nodded, and so we looked at one another and kept nodding, and the Rolling Stones came on again. “I see a red door and I want it painted black . . .”

He ordered another round for us.

“Did you c

ome to take your exams or what?”

“I promised my mother. If I flunk another year, I’ll sign up too.”

Suddenly there was a shot, right near my ear, and I saw Darko’s eyes grow wide and his jaw drop.

It was as if we were stuck in that moment for some time—that is, it took a little while for us to hear the voices and music again.

Some guy had shot a bullet into the ceiling. He’d been messing around with his Kalashnikov.

“C’mon, watch what you’re doing!” someone called out.

“Damn, sorry,” said the guy with the gun. He was buzzed. His hair was tied back in a ponytail. His uniform didn’t really fit properly.

“Let’s get out of here,” Darko said, finishing his two drinks.

“But where to?” I asked, keeping my seat. The absinthes and my stress pill had made me pretty lethargic. “Do you think something’s still open?”

He looked at me like he didn’t know what to do with me and said: “Let’s go to my place!”

We staggered off to Britanski Square in the pitch darkness.

* * *

At Darko’s apartment the roller blinds had been lowered all the way down, so he turned on an evening lamp on a nightstand next to the couch. He had one of those corner couches—probably leather, or imitation leather, in that awful yellowish color . . . Something I could only dream of having. He started rolling a joint on the glass coffee table. There on the table’s edge I noticed a transistor radio and batteries that had been readied for the shelter. Just like they’d said to do on television. Because a transistor radio would allow us to hear official announcements so we would know what was going on and everything would remain calm and under control. For instance: if the shelter were covered over by rubble, they would let us know that they were searching for us. He told me how in the early days he would run into the shelter with his transistor radio.

But now he’d already given up on that, he said. It had become annoying: our people sounded the sirens nonstop, but Zagreb wasn’t even being attacked.

First we lit up the joint, and then he put out some pancetta and bread on the table and we started eating. I didn’t realize how hungry I was.

He had wine. It was domestic. The grass, the eats, and the wine really relaxed us. So we started talking politics: Milošević, Tuđman, Europe, Americans and Russians, even Germans, the French and the English. It seemed to me that I had a better grasp on things, but I could tell he thought he did. And then he changed the subject and said he’d been seeing a girl recently.

“Why didn’t you say so?!” I interjected.

But he went on about how they’d met in the Concordia, and how at first he didn’t know that she was a Serb, because they’d hooked up fast, and she spoke like someone from Zagreb. “You know, she’s Zagreb through and through,” he said. She was a hairdresser, and their sex was out of this world—he said that a little more quietly, almost as if he were admitting that he was in love.

“And her daddy is in the military.”

“For real? Is he retired or—”

“Not retired one fucking bit. He’s in the JNA barracks over on Ilica Street. The National Guard is blockading them.”

“Aha, so that’s it!” I said.

“What’s it?”

“Nothing,” I said. “So, she’s out boozing because of that?”

“She really does drink a lot, I don’t know whether that’s the reason why. We met three weeks ago, and since then . . . Really intense, you know . . .”

“Wait. The guy comes home at night, and then goes back to the barracks in the morning, to his position?”

“No, no. They’re barricaded in there now. She doesn’t sleep at home either, they received threats. Her mother’s already gone, back to Serbia, to some town there where she’s from. She didn’t want to go. She says this is her home town,” he told me, staring at me. He was already pretty drunk.

“She doesn’t have it easy.”

“Sometimes she sleeps at a girlfriend’s place, and sometimes here,” he said, gesturing with his head.

“You mean she’s here?”

“She’s asleep in the bedroom.”

Right. I’d forgotten that he had a bedroom too.

Darko’s parents worked in Germany. The more fucked-up things got here, the better his apartments were: prices fell, but his parents kept sending the same amount of money. They probably didn’t count on a Serbian girl sleeping there, being as they were fairly big Croat patriots.

“You understand?”

“Yes,” I said, though I didn’t know what he was asking.

“And then today we were watching TV together and had a knock-down-drag-out fight. That’s when I left and signed up,” he said with a sigh, then took another drink of wine. “Really, I just can’t take that kind of thing!”

“What?”

“The Serbs. How they’re walking all over us. All that.”

“Ah,” I said. My head was swimming from all the information.

“Man, there are more of them and they have guns. But so what, fuck them!”

“Easy, she’ll hear you.”

“Fuck, I’m really crazy. What am I doing—what?!”

“C’mon, cheers!” I said, and raised my glass so he’d calm down, and we clinked our glasses. We were already drunk, but we continued swigging the wine.

Then the bedroom door opened and his girl appeared. She was in a short nightgown; she had good legs. I gaped a little. I could see a spark of pride in his eyes and a faint smile.

She nodded and went past into the bathroom.

“You see that?” Darko asked in a whisper, as if now I would understand his dilemma.

“Uh-huh.” I almost added, a little drunkenly, She’s really hot. But my next thought was, You can’t compliment someone’s girl like that.

She appeared again, and asked him: “You got any beer?”

“No, just wine,” he said, and passed her the joint he’d just lit back up. “This is my friend.”

She extended her hand. “Nataša.”

“Iggy,” I said.

“You mean Igor?”

“Fine,” I said. “Igor.” It was always the same.

She took a couple hits. “So what are you two doing?”

“We’re talking,” he said.

“We’re chatting,” I said.

“O-ho-ho,” she said, laughing. “Let’s chat!”

I watched her, probably like an idiot, thinking: Your old man had me in his sights today.

“Who’s chatting anymore, man?!” she said to me, as if to a fool. “There won’t be any more chatting!”

“He’s a real jokester. He failed the entrance exam for acting school twice; they didn’t realize he’s the new Woody Allen,” Darko said. As usual, he added: “And he’s studying traffic engineering.”

He always thought that was funny, and I did sometimes too. What are you studying? Traffic. Then everyone thinks of cars going back and forth. But worst of all was when he introduced me as a jokester. That carried certain obligations with it.

“I’m just a student,” I said to Nataša.

But she laughed again. “I’m just a student! Good one! An ordinary student. Terrific!”

“An ordinary student,” I repeated like an idiot.

“You’re good!” Nataša said. “That’s what I’ll say from now on: I’m just a student.”

“You can’t say it like a man,” I said.

“How should I say it then?” she asked. “Oh, I’m, like, a student! No, that sounds a little too . . . something . . . like someone could just fuck me. I’ll stick with I’m just a student.”

“Okay, you’re just a student.”

“Are you two crazy?” Darko asked, smiling.

“Yep, we’re just students,” Nataša said, and started laughing uncontrollably. I watched her, trying to understand . . . No, I thought, I didn’t say anything that was laugh-out-loud funny. The deal was probably that she wasn’t just a student. S

he is now a Serb above all, I thought. And, That grass hit you quick.

“We’re just taking classes, like lots of people,” I said, since the student thing had gotten such a good response.

She was laughing so hard she had to hold her belly. Me too. And Darko. It was infectious.

“I’m no ordinary student,” Darko said when the laughing had let up a bit. “I signed up today.”

“Where?” she asked, with laughing eyes.

“With the Croatian Defense Forces,” he said, looking away and still laughing. But if someone had photographed him he might have looked as if he were crying.

“Ooh, damn!” she said.

His laughter faded. “What about it?”

“Nothin’,” she said, crossing her arms below her breasts. I took a little look, as much as was allowed. How much is allowed? That was what I was trying to figure out, but . . .

“You don’t like it?” he asked.

“Look, it’s your business!” she snapped.

It seemed to me as if that day’s argument might be repeating itself.

“They don’t have weapons!” I said. I was trying to lighten the mood. “Maybe they won’t even call him up.”

She didn’t have a bra on.

They said nothing. They each looked in their own direction.

“And what, even if they do?” I said. “The Croatian Defense Forces isn’t a regular army . . . You can sign up, but you don’t have to.” He was looking at the radio that he’d prepared for the shelter. I scratched my head and went on: “Hey, you showed up, signed up, gave them a chance, and they let you go . . .”

I was trying to tone everything down, but he said: “Are you two fucking with me?”

“Us two?”

“Don’t mess with him, you can see he’s turned serious. He’s a soldier.”

“You can fuck off with that,” he said. Then he looked up and cried out in the voice of a righteous man: “Oh man, her father is in the JNA barracks, and what’s she lecturing me about? Warmongering. Every day.”

I didn’t know what else to say: they could sort this out on their own.

She sat down in an armchair and poured herself some wine. “My old man’s a fool.”

After a pause, she added: “And then I found you.”

Zagreb Noir

Zagreb Noir